Urban transit buses represent a prime opportunity for electrification. Their typical duty cycles allow them to be conveniently recharged at terminals, and the savings on fuel and maintenance can be enormous. Furthermore, cities around the world are revitalizing and beautifying their downtown districts, so getting rid of noise and diesel smoke is a welcome benefit.

Battery-electric buses are operating in pilot programs in dozens of cities in North America, Europe and Asia, and in EV hotspots such as California and China, they’re already being phased into regular service.

However, municipal transit authorities face the same dilemma that individual car buyers do: while an EV may save a lot of money over its lifetime, the purchase price can be almost double that of a legacy vehicle. Fortunately, there’s an elegant solution.

Complete Coach Works (CCW), founded in 1986, is one of the country’s largest remanufacturers of transit buses. The California company is now offering remanufactured buses with electric drive at prices comparable to new diesel buses, with the additional environmental benefit of recycling the chassis and many of the parts.

There are several reasons that a transit agency might choose to remanufacture vehicles, from replacing worn-out engines to modernizing older buses with new technology, such as accessibility features to comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act. These days, a growing number of transit authorities are remanufacturing buses in order to upgrade legacy diesel drivetrains to more modern options.

CCW’s Zero Emission Propulsion System (ZEPS) battery-electric buses fit the bill perfectly. Charged recently spoke with ZEPS Sales Manager Ryne Shetterly about the advantages of taking the remanufacturing route.

“We really like to stick to our model of sustainability,” says Shetterly. “By remanufacturing vehicles that are already in service, or that have already gone through a useful life period, we’re saving about ten times of raw materials, and that’s something that we take great pride in. It’s having a big impact on the environment. We’re re-using chassis that are in perfectly good working condition.”

CCW built its first prototype ZEPS bus about five years ago, and now has electric buses in operation in about half a dozen US cities, with several more on order. CCW’s biggest order to date (and the largest fleet of electric transit buses in the country) consists of 21 buses it sold to the Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation (IndyGo), which operates approximately 157 buses on 31 routes in Indiana’s capital.

“A lot of people are looking at that project as kind of the indicator of success,” says Shetterly. “For us to actually execute and deliver a successful project like that has really heightened interest, and we’re getting calls from all over the country.”

CCW remanufactures a lot of Gillig, New Flyer and Orion buses, but it works with anything and everything in the transit world. The team has worked with other alternative fuels in the past, including LNG, CNG, and “clean diesel” technologies. “We installed one of the first hybrid packages that was available way back in the day,” says Shetterly, “but that’s not a viable option anymore. We’re always trying to stay on the cutting edge of clean technology, but now we’re all in on electric.”

Shetterly wouldn’t say exactly what percentage of CCW’s business the electric buses represent, but said that it is “a healthy portion…and we do see it being a much larger portion of what we do in the future.”

An offer cities can’t refuse

The cost of a remanufactured battery-electric bus is in the neighborhood of what a new diesel bus would cost with all the options, Shetterly tells us. “We’re coming in at about $580,000. That’s about $200,000-$300,000 less than a brand-new electric bus from one of the OEMs that are currently in production.”

Savings on fuel and maintenance are expected to add up to about $440,000 over the useful life of the bus.

The ZEPS on-board charger (100 amp, 50 kW), is designed to require no special charging infrastructure beyond 480-volt, 3-phase electrical service, which would normally be installed at an overnight depot.

Some transit authorities send CCW their buses to be completely refitted, an option that is not only cheaper, but faster than buying new vehicles. “You can go buy a brand-new bus for X amount of dollars, or you can come to CCW and spend a fraction of that, and have a bus in six months, versus the standard 18-24 month lead time that you see with the OEMs.”

Another advantage of a remanufactured bus is that many of the components are already familiar to maintenance staff. “We’re taking a bus that has been on property for the last ten years or so, and the maintenance team is already familiar with how to take care of the preventive maintenance,” says Shetterly. “None of the parts are going to change, so there’s not going to be any new parts inventory required. The drivers are already familiar with the buses. We keep the OEM build as close as possible to where it was when it came off the line. We rebuild what we can rebuild – obviously some of the essential parts get swapped out for the electrical components, but mostly everything is going to stay the same.”

“The fact that it’s a refurbished bus with a chassis we currently operate in our fleet makes it practical in terms of interchangeability of parts – it’s a great benefit to us,” agrees Mario Delgado, Transit Director of McAllen, Texas, which bought two ZEPS buses. “The response from the drivers so far has been very good. They are excited about how quiet and smooth the ride is.”

The rebirth of a bus

The transformation of a bus begins by dismantling it down to the chassis level. The diesel engine, transmission, radiator and belt-driven accessories are removed, and the differential is remanufactured to a taller gear ratio of 6.1 from the existing ratio of 5.4. Shock absorbers, air bags, tie rod ends and wheel hubs are replaced with new parts. New composite flooring, seating, an electric air compressor and a power steering pump are installed.

Several upgrades help to maximize the vehicle’s operating range, including lightweight flooring and seats, lightweight aluminum wheels, low rolling-resistance tires, energy-efficient heating and cooling, and LED lighting.

The ZEPS bus has a 131 kW liquid-cooled electric motor. “The torque on it is just absolutely amazing,” says Shetterly. “You’re looking at about 1800 pounds of torque. So, it’s great for pulling grades – it operates really well on an intercity route, where there’s a lot of start and stop.”

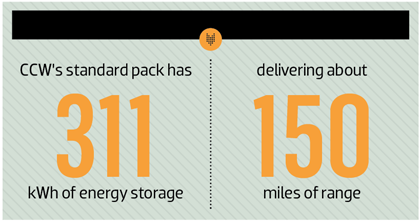

CCW uses Samsung lithium-ion battery cells, and offers a couple of range options. The standard pack has 311 kWh of energy storage (250 usable), which delivers a range of about 150 miles. It also offers a half-pack option: a 154 kW hour pack coupled with WAVE inductive charging technology (see sidebar).

Battery-electric technology is not suitable for every bus route. “You’ve got some transit buses doing 300 miles a day,” says Shetterly. “Right now, there’s really not an electric bus that will meet those needs. But with the progression in technology, and where the market is heading, it may be something that’s available in the not too distant future.”

Story courtesy of KSBW.com Action News 8.